In honor of the late Haskell Wexler(1922-2015), I thought I would post this essay I wrote in UCLA film school on Wexler's iconic film "Medium Cool," famous for its blending of fiction and reality against the backdrop of the 1968 Chicago riots. At once a forerunner of the "unscripted" reality TV genre and also a prophetic jeremiad in the vein of media critics Neil Postman and Marshall McLuhan (who inspired the title), Wexler's film was also pioneering in its handheld, verite style (which has now become commonplace). Below is my lengthy essay about the film, which I believe remains one of the quintessential American films of the 20th century. Cinema in the last few years of the 1960s was, like the culture at large, in tumult and transition. Countercultural notions of innovation abounded in cinema, particularly in Europe (the French New Wave, for example), and the proliferation of televised news (and the technology—smaller mobile cameras/equipment—that came with it) filtered down to a new sort of guerilla, vérité filmmaking. As mainstream society began to bring into question the hegemonic systems of control and even reality that were proving ineffective and disillusioning, so the film industry began to allow for countercultural critique, with pictures like The Graduate (1967, Embassy Pictures), Easy Rider (1969, Columbia Pictures), Zabriskie Point (1970, MGM), and The Strawberry Statement (1970, MGM).

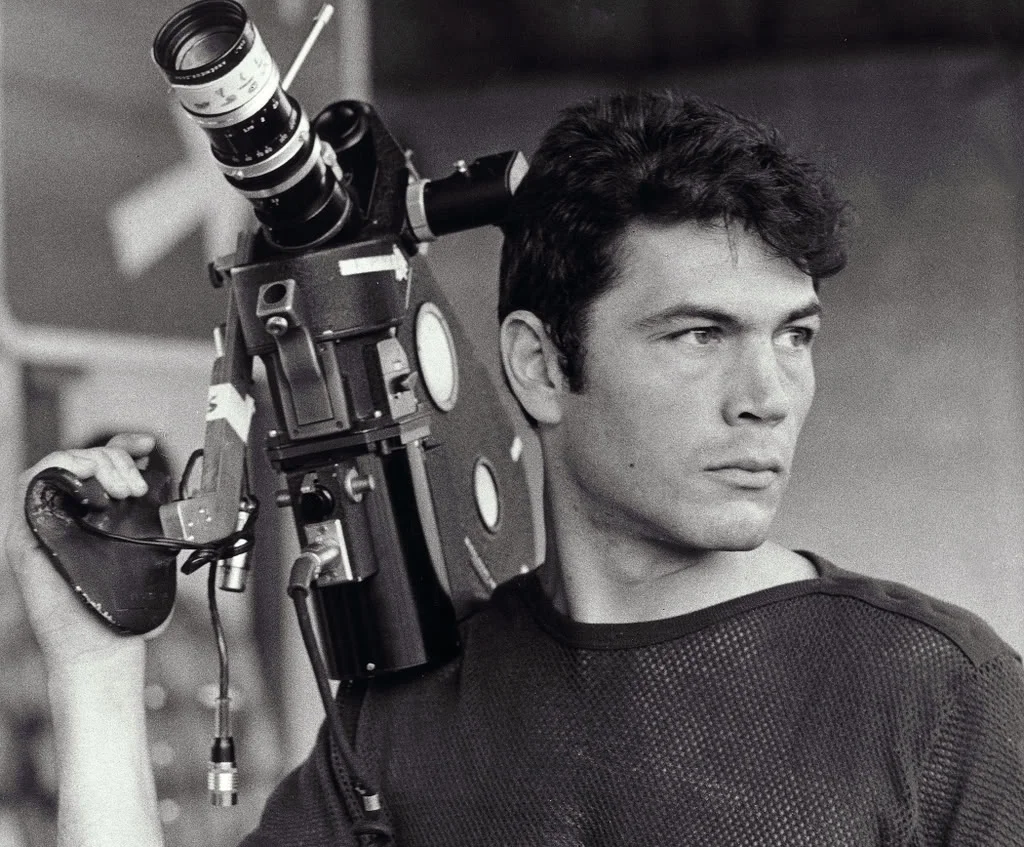

Perhaps most self conscious among this group was Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool (1969, H&J Productions, Paramount), which provided arguably the most comprehensive assessment of the fluctuating state of the world at the time. Medium Cool, about a roaming Chicago news cameraman (Robert Forster) capturing the headline-grabbing stories of 1968, was not only a hallmark film of the sixties and famously boundary pushing (in more ways than one), but it was also one of the most unique examinations of the changing media culture ever to be explored in cinema.

The Origins of Cool

In the late sixties, Haskell Wexler, a much-lauded cinematographer of such films as In the Heat of the Night and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolfe? (for which he won an Academy Award), was itching to direct his first feature. Wexler, a politically-active liberal with a penchant for ruffling the dominant culture’s feathers, wanted “to make a film which reflected the energy, the excitement that was being ignored, and which I felt so passionately about” in the tumultuous period of the Vietnam era.[1] He wanted his first feature to be a marriage between narrative fiction and cinema vérité that synthesized his broad experience in the art of film with his strong opinions about the goings-on in the world.[2]

1968 was a year that would for generations after be remembered as the climax of “the sixties,” the year when civilization was on the brink of collapse—or perhaps revolution. From January’s Tet Offensive in Vietnam, to the Columbia University shutdown and the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in the spring, it was clear to Wexler that his movie would have to incorporate current events. Knowing the film would be shot in Chicago in late summer, and anticipating that the Democratic National Convention to be held there in August would likely provide much fodder for his camera, Wexler was determined to incorporate whatever might happen into his film. Paul Golding, an editorial consultant on Cool, recalls reading an early version of the script back in January 1968 that had riots and demonstrations built in.[3] Wexler, who was familiar with the anti-war movement, knew enough people that were planning big demonstrations for Chicago that he could safely anticipate riots, though certainly not to the extent and scope that ultimately took place. From the earliest stages of the film, it was clear that Cool would be about, among other things, the interplay between script and reality, fiction and fact.

Before production actually began in Chicago, Wexler had already shot some footage with Forster and Peter Bonerz (who played soundman “Gus” to Forster’s lensman), following the two-man “crew” as they sought out—guerilla-style—footage of current events such as the Washington D.C. funeral of Robert Kennedy in June, and the muddy shanty-memorial, “Resurrection City,” on the mall in Washington in May. This footage was incorporated into Cool later to emphasize the film’s place in time (1968), as well as the thematic ideas of looking at reality through the lens of a news camera. Another pre-Chicago scene was shot at the National Guard training ground in Fort Ripley, Minnesota, on June 19, 1968. Wexler had received permission to shoot footage of Guard troops staging “practice riots” in preparation for what might happen in Chicago later that summer. Forster, Bonerz, and Wexler had free reign at Fort Ripley, and captured what would become a central scene in the film—an eerie “play version” of the Chicago riots that would take place a couple months later. It is interesting to look at the footage from Camp Ripley (there is a significant amount of extra footage never scene in the film[4]) and realize how perfectly this situation captured Wexler’s themes of the blurring of theater and reality. The Guard troops are dressed as “hippie/protesters” and ham it up for the cameras, acting like how they think the hippies might act in the inevitable clash with authorities in Chicago. Wearing costumes that include peace-sign jewelry, shirts with hand-drawn symbols and slogans of the hippie stereotype (“Flower Power,” Stars of David, Hells Angels, “Just Call me Egghead”), and toting posters that make fun of both Chicago and student protesters (“Separate Living Quarters for Polocks! (sic),” “Draft Beer not Students!”), they march arm-in-arm, singing We Shall Overcome, laughing boisterously all the way. Wexler recognized the significance of this footage, especially when juxtaposed with the real “performances” that he captured later in Chicago:

They [both the National Guard as hippies and later the hippies themselves] were doing theater… The whole idea of presenting ideas in dramatic, theatrical ways was something the anti-war movement knew very well… to get the attention of the media… Everyone’s putting on a show for somebody. In our culture, if you’re not on television, you don’t exist. [5]

When the production in Chicago commenced in July and August (Wexler would shoot a total of six weeks in the city), the interplay between fiction and documentary really escalated. Wexler and his stars shot many scenes just as written in the script, such as the notorious naked bedroom romp between Forster and Marianna Hill that would earn the film the dreaded ‘X’ rating. But even this scene—staged as it was—had an organic, documentary feel to it. According to Wexler, in order to make his actors more comfortable (especially Forster) with their nudity on camera, he cleared the set and himself stripped naked; chasing his actors around with a handheld camera and nothing else.[6]

Indeed, Wexler took great pains to ensure that even when his scenarios were “scripted,” they were still treated with as little technical distance as possible. Wexler used no sets, few artificial lights, and only natural sound. Sometimes the un-staginess confused critics, who often praised certain “well-done set pieces,” not realizing that they were not sets at all, but real places full of, not extras, but real people.[7] Wexler tried to use only local people as “actors” (apart from the starring roles), and used his friend and Chicago-aficionado Studs Terkel to connect him, for example, with the poor Appalachian communities of Uptown, where they plucked young Harold Blankenship out of the slums for a few weeks and had him star as himself opposite Verna Bloom as his mother and Forster as his surrogate “dad.” Wexler was so impressed with the natural abilities of Blankenship in front of the camera that he improvised several scenes with the young actor, most famously the scene when Forster takes the boy back to his mod apartment, allows him to explore an entirely foreign strata of domestic space, and lets him clean up by taking a shower. “Harold’s shower in the film is the first shower he’d ever taken in his life,” noted Wexler.[8] It was one of many moments in the film where the reality of the “scene” was awfully close to the reality in general.

There are other moments in the production that witnessed the collision of reality and fiction by tapping into the social ferment and civic tension of Chicago that summer. There was footage shot of Verna Bloom’s character attending a real-life workers’ organizing meeting in Chicago, for example, with a young Jesse Jackson giving a “call-to-arms” speech (this scene was cut, though Jackson still appears briefly in the Resurrection City scenes). And then there is the scene in which Forster and Bonerz have to venture in to Chicago’s ghetto to interview a black taxi driver about a story they were covering for the news. Wexler, who admits that behind a camera he feels “indestructible,”[9] recalls the scenes with the Black Panthers as the most tense in the whole production. In the early script, it appears that Wexler anticipated that this scene would be a challenge to shoot, writing:

NOTE: Since most of the words in this scene need to be accurate and contemporary Negro dialogue, no attempt is made here to write those words. The AD LIBS will be obtained on location by recording an improvisation session, then by committing to the script the most appropriate remarks…[10]

And by all accounts, this is how it happened. Wexler found and recruited real Black Panthers by promising them a chance to sound off for the cameras, ironically, about how the media ignored the voice and plight of the urban black man. The scene is remarkable in the way that it plays upon media issues of representation—by giving direct-to-camera face time to marginalized blacks—but also in the way that its portrayal of the tension between “exploitive” white mediamen and suspicious black “militants” mirrors the actual tension of the situation of Wexler and his actors invading the black urban ghetto for arguably exploitive ways (getting the money shot that was part of a larger script).

Of course, the culmination of the film’s real/unreal dialectic came when the bedlam of the Democratic Convention began. As protesters assembled throughout the city on August 28, 1968, Wexler was covering it with all he could muster (three cameras), justifying his extensive footage of the protests/riots by making it the setting for the climactic plot point of the film—when Verna Bloom’s character sets out on foot to look for her missing son (Blankenship). Wearing a memorably bright yellow dress (“totally serendipitous; a happy accident”[11]), Bloom meanders through the crowds of protesters, looking alternately determined to find her son (in character, she goes up to unknowing Chicago cops and asks about her “missing son”) and ponderously intrigued by what was happening around her (in footage that was scrapped, she actually stops to pet a snake that was draped around a hippie’s neck[12]… no urgency there). In watching these scenes—of a fictional character being followed by a camera, through masses of people and chaotic situations that were being filmed by numerous other cameras for “nonfiction” purposes, one cannot help but see Wexler’s vision for Cool being crystallized. As Bloom comments on the surreal experience, “I was playing a part in a make believe movie in a real situation.”[13]

Other moments of the riot shoot drove home the surreal reality of the situation in more disturbing ways. Bonerz, who remembers being more afraid of the cops than anything (“They seemed literally angry from the bottom of their boots” [14]), is shown at one point tending to an actual injured protester, bleeding from a head wound. Both of the film’s lead actresses, Verna Bloom and Marianna Hill, were harassed by the police and arrested on suspicion of prostitution.[15] The most famous moment of frightening reality, however, came when Wexler was filming some rioters being assaulted by armed men, who shot tear gas at the crowd, with one canister directed right at Wexler’s camera. Unlike the simulation at Fort Ripley, this time it was real, and we are reminded of this fact with the famous off-camera line, spoken by assistant Jonathan Hayes—“Watch out Haskell! It’s real!”—which, as it turned out, was recorded later and added in for effect, even though Wexler maintains that those were the exact words going through his head as he was gassed. Regardless, the gassing itself was real, and Wexler was temporarily incapacitated and his eyesight permanently damaged. “My assistant picked up the camera and shot Hayes and me on the ground,” Wexler recalls. “I keep a still from that footage in my office.”[16] The violence of the protests—and the camera’s capturing of it—certainly contributed to the statement Wexler wanted to make about the media’s (and to an extent, the audience’s) detached view of reality, especially violence, when seen through a lens or on a television set. Wexler, who references both Kennedy assassinations in Cool, reflects on the desensitizing effect of the media:

The first time that millions of Americans actually saw a man being killed was when Ruby shot Oswald. They gasped and said, ‘I don’t believe it.’ But then they saw it replayed and replayed, with the TV announcer saying, ‘Now watch Ruby’s hand, now watch officer so-and-so’s arm as it drops to his side, see Oswald’s look of anguish as he doubles up.’ The public was watching a scene charged with drama, but one filtered through a glass, a glass protecting them from what people in the past had experienced. When reality comes to you that way, it comes minus one ingredient, and that ingredient is human emotion.[17]

Wexler, who admits in numerous places that Forster’s character of John Cassellis, an emotionally-detached cameraman more obsessed with shooting great footage than anything else, is quite a bit like himself (“I am that cameraman”[18]), thus became further galvanized by the violent scene in Chicago, but also the depths of his own character that were being mined.

Critical Reaction: Cool is Hot

Despite Paramount’s fears that the pro-counterculture stance of Cool would alienate many audiences, it turned out that the film’s place within the burgeoning genre of “60s rebel films” was a marketing virtue. Despite the film’s relatively small box-office impact, Richard Corliss, writing in Film Quarterly, hailed the film as significant in film history because it “is making more money than its recalcitrance would have suggested,” even with its various political and sexual taboos. Corliss regarded Cool, along with Easy Rider and Alice’s Restaurant, as a “financial breakthrough” that “may portend a small revolution in commercial film-making.”[19] Other critics noted the comparisons to Easy Rider and other envelope-pushing films of the era. “It is less clever than Midnight Cowboy and less indulgently and emotionally personal than Easy Rider, wrote Charles Champlin for the L.A. Times, “but it asks larger and more disturbing questions than either.”[20] John Mahoney, in the Hollywood Reporter, called the film “McLuhanized domestic Jacopetti” and noted how the film represented corporate cooptation of the counterculture: “[Paramount] has proven that a company can simultaneously subsidize and profit from the revolution.”[21]

Others saw the film as part of the Americanized version of the French New Wave, especially in its utilization of documentary conventions and fiction/non-fiction reflexivity. “More and more filmmakers are leaving the studio behind them to find and tell their stories against actual backgrounds, often using what they discover to flesh out their films,” perceived Hollis Alpert[22] of Cool, as well as Coppola’s road movie, The Rain People. Many critics saw the influence of Antonioni and especially Godard on Wexler’s film (catching the visual references like the Jean-Paul Belmondo poster in Forster’s apartment and the final “turn the camera on the viewer” shot), underscoring the extent to which Cool was consciously toying with notions of mediated reality and the camera’s gaze.

In general, critics were very kind to Cool, offering pull-quote praises that more than rewarded Wexler’s struggle to get it released. Critics called Cool “more than a ‘message film’; it is a great film”[23] that “strikes at the very structure of our existence—our reasons for being alive.”[24] Even when critics were not quite so generous with some aspects of the film (the ending was particularly criticized), most responded well to the film’s fusion of fiction and real life. Gordon Cow of Films and Filming felt that the use of unfamiliar actors was especially conducive to the sense of realism, and praised the incorporation of “vérité interviewing, perfectly dovetailed to eliminate any sense of division between fiction and fact.”[25] Another critic wrote that “never before had so complete an attempt been made to mix theatrical and actual events within the framework of a single motion picture.”[26]

Not all were as convinced that the fusion worked, however. Richard Schickel wrote in Life that “I am not sure Mr. Wexler has entirely solved the esthetic and technical problems that arise when fictional characters are juxtaposed with great events… [Wexler] never quite succeeds in melding his people believably with his superb documentary footage.”[27] Indeed, the most common general critique of Cool was that it felt rather disjointed and overly ambitious, with many great things going on but not a lot of cohesion. While some critics, like Vincent Canby of the New York Times, saw the film’s schizophrenic nature as a virtue (“a kind of cinematic ‘Guernica,’ a picture of America in the process of exploding into fragmented bits of hostility, suspicion, fear and violence”[28]), others saw the same pastiche as somewhat problematic (“a cataclysmic kaleidoscope of thunderhead emotions”[29]). Stanley Kauffmann noted, in New Republic, that the film suffered from its inability to make connections: “There may well have been a connection between the television age and those youthful protests—as McLuhan has maintained—but it is utterly unestablished here.”[30] Similar complaints questioned the inclusion of “rock music interludes and gratuitous sex play” that were “irresponsibly meddling toward no purpose,”[31] especially trivial when cut in between references to JFK, Martin Luther King Jr., politics, and other “important” issues. Many felt the film—like the year 1968—was almost too loaded and paradoxical. The New Yorker review best summed up this complaint:

“Medium Cool” is nothing if not on the nose, and truly loaded with issues—Vietnam and Appalachia and the child (who later gets lost in the Conventions riots), and McLuhan notions about the “cool” medium of television, and Mayor Daley’s henchmen, and the nature of reality, and the vanishing sense of personal responsibility.[32]

What these criticisms fail to realize, however, is that to acknowledge the disconnectedness and fragmentation of Cool is perhaps the most germane argument that can be made for the film as a successful representation/critique of modern media culture.

Medium Cool as Self-Conscious Media Critique

Medium Cool is above all else a meditation on the nature of mediated reality. In order to truly capture the events and mood of 1968—a year that was made all the more traumatic by its ubiquitous presence on the evening news—Wexler wisely approached the production with a roaming, story-seeking reporter’s instinct. The film's very form—a sometimes-arbitrary collection of plotlines, images, and sequences both scripted and improvised—comes across as disjointed and meaningless, only because “disjointed and meaningless” were apt words to describe the media in Wexler’s mind. Though the name and concepts explored in the film came from Marshall McLuhan, perhaps McLuhan’s heir in media theory, Neil Postman, better captures the point that Cool was trying to make:

If I were asked to say what is the worst thing about television news or radio news, I would say that it is just this: that there is no reason offered for why the information is there; no background; no connectedness to anything else; no point of view; no sense of what the audience is supposed to do with the information. It is as if the word “because” is entirely absent from the grammar of broadcast journalism. We are presented with a world of “ands,” not “becauses.”[33]

It is this fractured nature of television—a medium chopped into bite-sized segments and commercials to alternately amuse and sell products—which Cool is bringing into question. As Vincent Canby points out, the character of John Cassellis is able to separate the act of shooting film from an understanding of the meaning of what is being recorded, a dissonance that defines the medium: “The televised image certifies the reality of events and, at the same time, removes them by equating their meaning to that of the commercials—the cheerful haiku—that frames them.”[34] It is this psychological distance, Wexler’s notion of being “indestructible” behind the camera lens, which is the central existential contribution of Cool.

Beyond being merely a film that captures a particular moment of history in extraordinarily artful ways, Medium Cool offers us a thoughtful examination of our position as spectators of and performers for an ever-present media. The film is more relevant now than ever, in our Youtube, cell-phone-camera age where nothing goes undocumented and no public action is enacted free of an awareness that, as the final lines of Cool repeat: “The whole world is watching. The whole world is watching…”

Footnotes

[1] Wexler quoted in Look out, Haskell, It’s Real: The Making of ‘Medium Cool,’ prod. and dir. Paul Cronin, 60 min, Sticking Place Films, 2002, videocassette.

[2] Judith Shatnoff, “Stay With Us, NBC…” Film Quarterly 23:2 (Winter 1969-70): 47.

[3] Golding notes this in the 2001 commentary track to Medium Cool, prod. and dir. Haskell Wexler, 110 min, Paramount Home Video, 2001, DVD.

[4] References to extra Medium Cool footage refer to the collection of behind-the-scenes 35mm footage now archived (and available to view on DVD) in the UCLA Film and Television Archive. DVDs #2590, #2591 and #2592.

[5] Wexler quote from Look Out, Haskell…

[6] Frank Thompson, “Running Hot and Cool,” Pulse! March 1995, p. 90.

[7]The New Yorker review (“The Current Cinema: Getting Warm,” 9 September 1969, p. 143), for example, refers to the roller derby scene as a “well-done set piece,” even as it is specifically noted by Haskell Wexler in the DVD commentary as having been shot at “real rollergames,” in order to portray another example of “violence for show; violence for excitement.”

[8] Wexler notes this in both the DVD commentary and in Look Out, Haskell…

[9] Wexler says this in Look Out, Haskell…

[10] Wexler, Undated early script. Kwik Script Service. 97pp. Housed in UCLA Arts Special Collections, Motion Picture Script Collection. Box F-663, Collection 73. pp 53, 54.

[11] Verna Bloom recalls this in Look Out, Haskell… of her wardrobe choice for that day of shooting in Chicago.

[12] Archival 35mm footage from UCLA collection (DVD #2591)

[13] Bloom quoted in Look Out, Haskell…

[14] Bonerz quoted in Paul Iorio, “Reliving the '68 Chicago Riots; Haskell Wexler's ‘Medium Cool' mixed reality, fiction at the Democratic National Convention,” The San Francisco Chronicle, 6 September 1998, p. 52.

[15] Thompson, p. 90.

[16] Wexler quoted in anon., “Cool Hand Haskell,” Cable Choice, May 1989.

[17] Wexler quoted in Guy Flatley, “Chicago and Other Violences,” The New York Times. 7 September 1969.

[18] Wexler says this in Look Out, Haskel…

[19] Richard Corliss, “Haskell Wexler’s Radical Education,” Film Quarterly 23:2 (Winter 1969-70): 51.

[20] Charles Champlin, “‘Medium’ With a Message,” Los Angeles Times, 21 September 1969, p. 20.

[21] John Mahoney, “Paramount’s ‘Medium Cool’ Not That, but Not so Hot,” The Hollywood Reporter, 24 July 1969.

[22] Hollis Alpert, “The Film of Social Reality,” Saturday Review, 6 September 1969, p. 44.

[23] Deac Rossell, “‘Medium Cool’: Wexler on violence,” Boston After Dark, 17-24 September 1969, p. 2.

[24] Nadine Edwards, “‘Medium Cool’ Sizzling Screenfare,” Hollywood Citizen News, 26 September 1969.

[25] Gordon Cow, “Medium Cool,” Films and Filming (April 1970): 20.

[26] Anon., “Wexler becomes Auteur with his ‘Medium Cool,’” Foreign Cinema, 26 September 1969.

[27] Richard Schickel, “Film for Us Voyeurs of Violence,” Life, ca. 1969.

[28] Vincent Canby, “Real Events of ’68 Seen in ‘Medium Cool,’” The New York Times, 28 August 1969, p. 46.

[29] Edwards.

[30] Stanley Kauffmann, “Stanley Kauffmann on films,” The New Republic, 20 September 1969, p. 20.

[31] Mahoney.

[32] “The Current Cinema,” p. 143.

[33] Neil Postman, Building a Bridge to the Eighteenth Century (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999): 94.

[34] Canby, p. 46.